Throughout her career as a nonprofit executive, award-winning executive producer and producer/director, broadcast programmer, curator, teacher, and writer, Cara has championed the leadership role of artists in society, and worked to harness the power of cultural...

Leia em portugués | Lea en español

Funders, activists and movement leaders need to understand what happens in the field of narrative during a time of crisis and disruption, and prepare ahead of time rather than scrambling to respond after a disruptive event takes place. Here are five factors we need to keep in mind..

— Brett Davidson, Narrative Lead at the International Resource for Impact and Storytelling

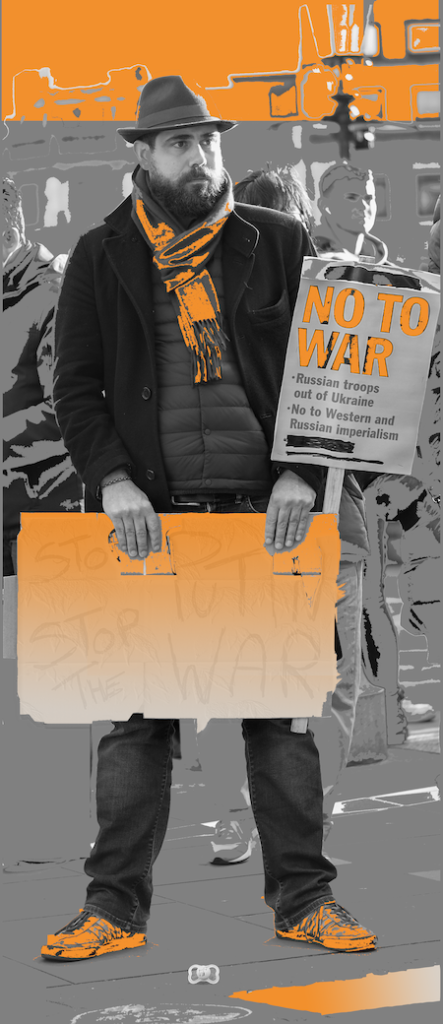

Watching tragedy unfold in Ukraine, I have been thinking about the powerful, rapid, and often unexpected impact that major, shocking events can have on narratives that underpin our understanding of the world. While narrative and culture change work tends to take years, events have the power to bring about rapid change, often in unexpected ways.

In 2011 the Fukushima nuclear disaster changed the conversation about nuclear power. It still resonates more than a decade later. The murder of George Floyd sparked a global protest and placed policing and structural racism at the top of the public agenda. Covid-19 led to a rethink about a whole bunch of things: health care, work, the economy, mutual responsibility. Arundhati Roy famously talked about the pandemic as a rupture with the past, a portal through which we could create a new world. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has disrupted the narrative about Europe, about refugees, and about the very nature of political leadership.

But events don’t shift narratives and conditions by themselves. Liz Manne’s excellent guide to narrative strategy talks about storytelling as the key route to shifting narrative. This holds true for shocking events—so much depends on the stories we tell about them, how we understand and interpret them.

Funders, activists and movement leaders need to understand what happens in the field of narrative during a time of crisis and disruption, and prepare ahead of time rather than scrambling to respond after a disruptive event takes place.

Here are five factors we need to keep in mind.

1. We rely on familiar stories

When shocking events occur, we try to understand them using stories we already know well. For example, often overlaying the story of Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s attack, is the much older one of David versus Goliath—the under-equipped hero bravely standing up against a bigger, stronger bully. When Covid-19 first caused a major global shutdown, one of the stories most immediately available to us came from countless dystopian movies and novels: widespread devastation and everyone for themself, pitted against one another for survival.

As we think about possible future shocks, we need to consider the familiar stories people are likely to turn to, ask ourselves whether these are ones we want to reinforce or counter, and plan accordingly. The Crisis Handbook, released recently by Greenpeace East Asia’s Mindworks Lab, offers a step-by-step guide on how to do this.

2. Hidden narratives reveal themselves

Shocking events can act like an earthquake, shifting the ground beneath our feet. They lay bare the layers of submerged assumptions that usually operate invisibly—revealing the real narratives at play rather than the ones we pretend to operate by. In the case of Ukraine, as Trevor Noah and Moustafa Bayoumi have pointed out, remarks by many American and European commentators and journalists starkly revealed the racist narratives at play behind the shock that this was happening in Europe – as if that made it different from the daily hell of conflict in Yemen, Syria, Afghanistan or Palestine.

As shocking as such media commentary is, it merely reveals prevailing narratives that have existed all along, hidden under a veneer of liberal respectability. Now that they are in the open, we can confront and deal with them. How will we do that, both today and the next time international hypocrisy is exposed?

3. Narrative complexity gets lost

One of the challenges facing those attempting to critique problematic narratives is that in a crisis narrative battle lines tend to harden, and there is often little tolerance for nuance and complexity. For example, those offering correctives to the racist media coverage of Ukraine, such as this piece by Moky Makura of Africa No Filter, have to deal with Twitter trolls accusing them of being tone deaf, or trying to divert attention from the war.

In the news and on social media, contrasting attitudes to Covid-19 are debated in terms of deepening political divisions not only between conservatives and liberals, but apparently also within these camps. We seem unable to have a collective, complicated conversation about risks, trade-offs and how we might create a more caring society. How do we prepare the ground, and what cultural organizing do we need to do now to create and hold the space for future challenging and complex conversations in a time of crisis?

4. Power and voice matter more than ever

The narratives that take hold and last once a new order settles in will depend on who has the voice and the power to be heard. This is where power-building comes in—including through cultural organizing—another element that Liz Manne considers critical in narrative change. What are we doing now to support unheard and excluded voices, to strengthen alternative media, to create a culture of curiosity and listening?

5. Actions do speak louder than words

Actions provide the raw material for stories played out in real time. They matter all the more in a crisis because when we are disoriented we look to others for cues on how to respond. This is the principle of social proof, first articulated by Robert Cialdini. An example is President Zelenskyy’s decision to stay in Kyiv rather than leave for a safer location, which transformed international coverage about him almost overnight – from being seen as someone ”in over his head” to being cited as an exemplary leader. The new narrative about Zelenskyy is so powerful that every subsequent action is taken as confirmation of his heroism—to the point where the New York Times talks about the Ukrainian president’s T-shirt as ”a symbol of the strength and patriotism of the Ukrainian people.”

Planning for the unexpected

As Naomi Klein pointed out in The Shock Doctrine, powerful interests have long used crises to entrench their power. Dominant narratives justifying that power are resistant to change. Despite the Black Lives Matter protests, police killings continue, and there has been a backlash in the US to calls for major police reform. Covid19 has not led to a better world. Universal healthcare remains a dream, while governments set up new forms of surveillance under the guise of pandemic preparedness. Europe’s new, welcoming approach to refugees may very well end as soon as the next boat full of African refugees crosses the Mediterranean.

We cannot afford to walk through another portal “dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and … dead ideas.” Funders need to help ensure the field is ready to advance progressive narratives the next time we are faced with a destabilizing crisis, and the next, and the next. As Nassim Taleb argued in his book The Black Swan, we need to build shocking events into our strategies and models of change.

Unpredictable events are difficult to build into strategy. But while we don’t know what exact form shocking events will take, we can be sure they will take place. The next nuclear disaster, climate catastrophe or pandemic should not take us by surprise. We need to be prepared, to understand what happens in the narrative terrain when shocking events happen and to be ready to act when they do.